45

Source: De Beers

F I G . 2 8 :

D I AMOND PROJECT P I PEL I NE ( 20 1 4 - 20 1 7 )

Note:

All data estimated based on best available public information as of May 2014

DEPOSIT NAME

OWNER(S)

DISCOVERER AND

YEAR OF DISCOVERY

COUNTRY STATUS

EST. FIRST

PRODUCTION

AVERAGE ANNUAL

PRODUCTION

(MCTS)

ADC (1997)

Development 2014

4

Grib

Lukoil Oil Company

ALROSA (1994)

Development 2015

2

Botuobinskaya

ALROSA

ALROSA (1982)

Development 2015

1

Karpinsky-1

ALROSA

Mountain Province

Diamonds (1995)

Permitting 2016

5

Gahcho Kué

De Beers/Mountain

Province Diamonds

Ashton (2001)

Permitting 2017

2

Renard

Stornoway, Newmont

Rio Tinto (2004)

Pre-feasibility 2017+

2

Bunder

Rio Tinto

Falcon Bridge

(1981)

Construction 2014

0.4

Ghaghoo

Gem Diamonds

Uranerz (1988)

Feasibility

2017+

2

Star-Orion South Shore Gold Inc

Russia

Russia

Botswana

India

Canada

Canada

Canada

Russia

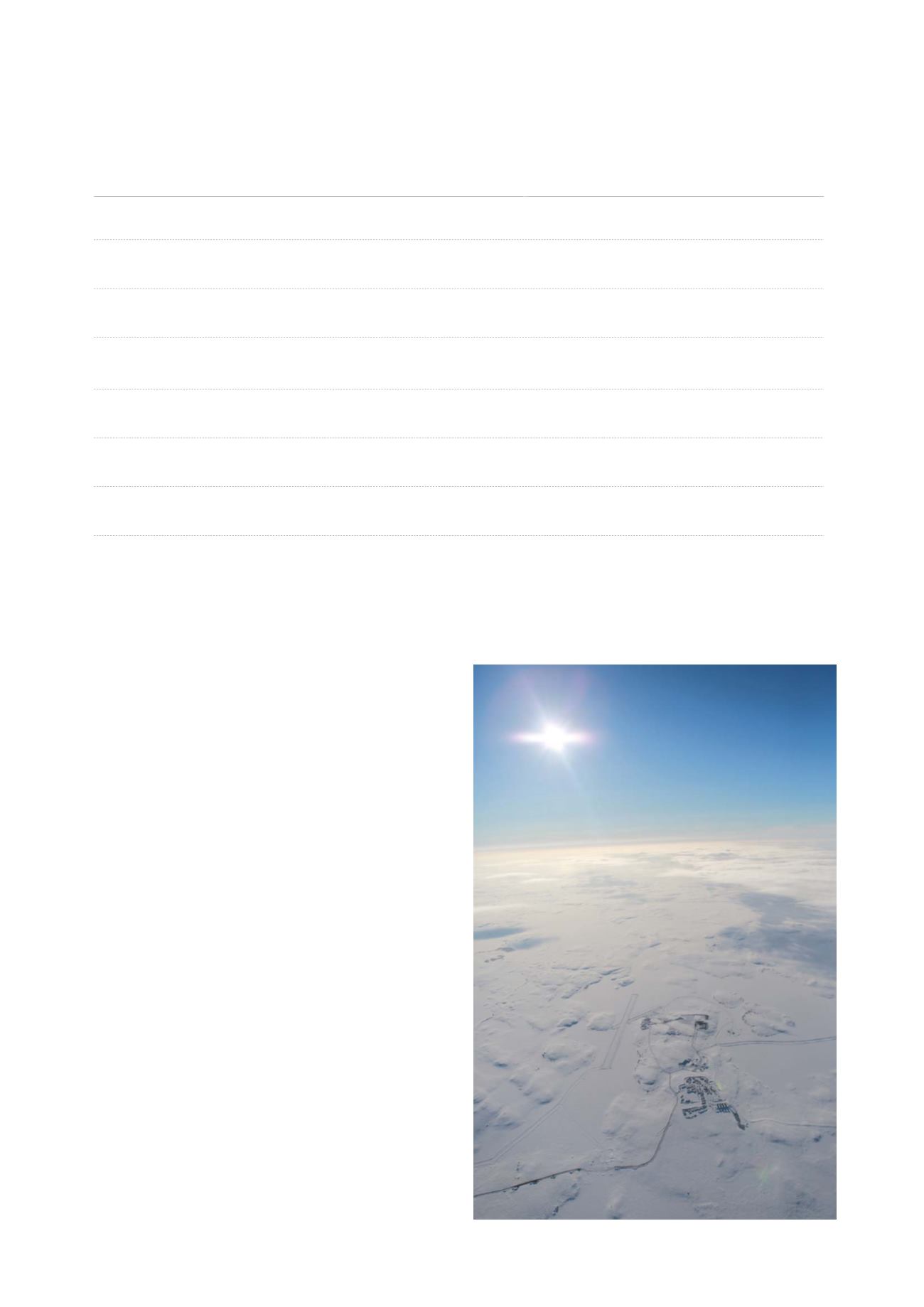

In order to make a difference to global availability,

any discovery would have to be substantial – even the

largest of new projects under development, Gahcho

Kué, will only expect to add approximately five

million carats per year at its peak of production,

about three to four per cent of annual global

production (see Fig. 28).

Even if new discoveries were made, the impact of such

discoveries on production levels would be likely to

be slow. From 1950 to today, it took an average of

14 years between the discovery of a diamond deposit

and the start of production. For projects currently

in development, however, this time is even longer:

it will take more than 20 years from discovery to first

production. Gahcho Kué, for example, was discovered

in 1995, but is not projected to enter production

until late 2016.

Diamond production is also becoming increasingly

challenging as mining moves towards deeper, less

profitable and more remote sources. This trend

is explored further in the ‘In Focus’ section, ‘The

miracle of production’.